This post was contributed by Dr Iroise Dumontheil of Birkbeck’s Department of Psychological Sciences, and co-author of the newly published study “Multitasking during social interaction in adolescence and early adulthood”. The paper, published in Royal Society Open Science, can be read here. Click here to read the news article

Humans are social beings. We have evolved to function in groups of various size. Some researchers argue that the complexity of social relationships which require, for example, remembering who tends to be aggressive, who has been nice to us in the past, or who always shares her food, may have been an evolutionary pressure leading to the selection of humans with bigger brains, and in particular a bigger frontal cortex (see research by Robin Dunbar).

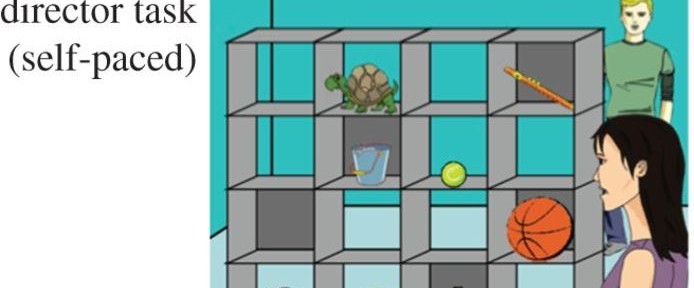

However, we do not always take into account the perspective or knowledge of a person we are interacting with. Boaz Keysar and later Ian Apperly developed an experimental psychology paradigm which allows us to investigate people’s tendency to take into account the perspective of another person (referred to as the “director”) when they are following his instructions to move objects on a set of shelves. Some of the slots on the shelves have a back panel, which prevent the director, who is standing on the other side of the shelves, from seeing, and knowing, which objects are located in the slots. While all participants can correctly say, when queried, which object the director can or cannot see, adult participants, approximately 40% of the time, do not take into account the view of the director when following his instructions.

In a previous study, Sarah-Jayne Blakemore (UCL), Ian Apperly (University of Birmingham) and I, demonstrated that adolescents made more errors than adults on the task, showing a greater bias towards their own perspective. In contrast, adolescents performed to the same level a task matched in terms of general demands but which required following a rule to move only certain objects, and did not have a social context (read the study here).

The Royal Society Open Science journal is publishing today a further study on this topic, led by Kathryn Mills (now at the NIMH in Bethesda) while she was doing her PhD with Sarah-Jayne Blakemore at UCL. Here, we were interested in whether loading participants’ working memory, a mental workspace which enables us to maintain and manipulate information over a few seconds, would affect their ability to take another person’s perspective into account. In addition, we wanted to investigate whether adolescents and adults may differ on this task.

What would this correspond to in real life? Anna is seating in class trying to remember what the teacher said about tonight’s homework. At the same time her friend Sophie is talking to her about a common friend, Dana, who has a secret only Anna knows. In this situation, akin to multitasking, Anna may forget the homework instruction or spill out Dana’s secret, because her working memory system has been overloaded.

Thirty-three female adolescents (11-17 years old) and 28 female adults (22-30 years old) took part in a variant of the Director task. Between each instruction given by the director, either one or three double-digits numbers were presented to the participants and they were asked to remember them.

Overall, adolescents were less accurate than adults on the number task and the Director task (combined, in a single “multitasking” measure) when they had to remember three numbers compared to one number. In addition, all participants were found to be slower to respond when the perspective of the director differed from their own and when their working memory was loaded with three numbers compared to one number, suggesting that multitasking may impact our social interactions.

Find out more

- News article: Adolescents are less adept at multitasking than adults, psychological study suggests

- Read the study: “Multitasking during social interaction in adolescence and early adulthood”

- Dr Iroise Dumontheil

- Department of Psychological Sciences

- Royal Society Open Science

*Image caption: Presentation of multitasking paradigm (image published in Royal Society Open Science paper). For each trial, participants were first presented with either (a) one two-digit number (low load) or (b) three two-digit numbers (high load) for 3 s. Then participants were presented with the Director Task stimuli, which included a social (c) and non-social control condition (d). In this example, participants hear the instruction: ‘Move the large ball up’ in either a male or a female voice. If the voice is female, the correct object to move is the basketball, because in the DP condition the female director is standing in front of the shelves and can see all the objects, and in the DA condition, the absence of a red X on the grey box below the ‘F’ indicate that all objects can be moved by the participant. If the voice is male, the correct object to move is the football, because in the DP condition the male director is standing behind the shelves and therefore cannot see the larger basketball in the covered slot, and in the DA condition the red X over the grey box below the ‘M’ indicates that no objects in front of a grey background can be moved. After selecting an object in the Director Task, participants were presented with a display of two numbers, one of which corresponding to the only number (e) or one of the three numbers (f), shown to them at the beginning of the trial. Participants were instructed to click on the number they remembered being shown at the beginning of the trial.